The early history of water injection into internal combustion engines

Posted on sam. 04 novembre 2017 in engineering

Introduction

It is quite usual for authors of papers dealing with water injection applied to internal combustion engines (ICE), to date back the invention of this process to its famous application on some supercharged WW2 aircraft engines1. However, this idea actually dates from the very beginning of the ICE history, and its initial goal was quite different from the current one, mostly related to pollutions mitigation. But before getting to the heart of the matter, let us say few words about the early ages of ICE.

According to Zima2, the first ICE were developed during the second half of the XIX century as alternative sources of mechanical power, cheaper than the expensive steam engines. Logically, their practical use were based on available and inexpensive fuels as well. The fuels consumed by such engines were then often heterogeneous, composed by gaseous (hydrogen, lighting gas, liquid heavy oils) and sometimes solid components, as coal dusts3. The nowadays usual light fractions of crude oil, including gasoline, have been indeed available for engines only since the late 1800s4. Combustion processes of such fuels were thus often ‘brutal’, producing too high temperatures and were difficult to control. This issue led some engineers of these days to look for a way to dilute and ‘slow down’ the chemical energy hence released.

The Lenoir engine

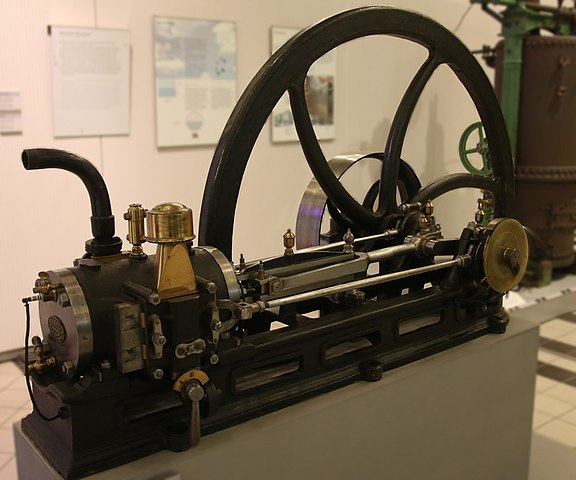

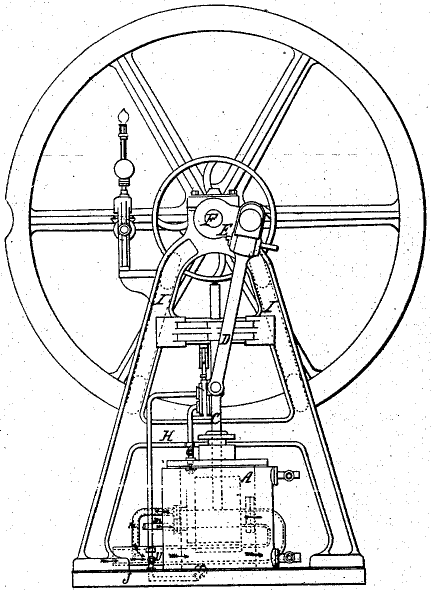

Probably because it has been the first ICE to be commercialized at a relatively large scale, with about 5000 engines built, the Lenoir engine (as the one presented below), invented by the Belgian engineer Étienne Lenoir, is one of the most famous5. Its ‘three-stroke’ thermodynamic cycle, without any compression stroke before the combustion one, is also quite well known.

What is less known yet, is that Lenoir also proposed, in a French patent6 filled in 1861, to inject steam or vapor spray into the engine cylinder in order to ‘cool it down’. According to Clerk7 (inventor of the first two-stroke engine, btw) though, the Lenoir’s idea was based on his erroneous understanding of the nature of gaseous explosions. Lenoir supposed that the performances of his engine would benefit from a ‘slowing’ of the explosion phenomenon, so the water injection system.

Despite this proposal, I did not find any mention in the literature to a practical implementation of such improvement on an actual Lenoir engine. This idea has been effectively setup on a real engine though, not by Lenoir but by his first contestant: Pierre Hugon.

The Hugon engine

In a US patent8 filed in 1865, Pierre Hugon has indeed proposed to inject liquid water, and not steam9 into the engine cylinder in order to ‘impart to the engine a more regular action and prevent the grease of lubricating substance from being burned‘. The first experiments of such a process have been led on July 20, 1866, at the French Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers (CNAM) in Paris, under the direction of professor Henri Tresca10.

Experiments having been done with and without water injection, Tresca and his fellows have noticed a difference in the indicated diagram (\(p,V\)) of the engine, as well as a decrease of the exhaust gas temperature. Nevertheless, they conclude on a interest of such process mostly for the conservation of some engine internal parts and for aiding lubrication. Clerk, incidentally, arrived at the very same conclusion in his book from 1897: ‘Devices proposed for increasing power by the injection of water spray, and steam, in various ways failed to produce good effect except in aiding lubrication‘.

Conclusions

Because of their similar will to better control the combustion processes occurring inside their contestant engines, Lenoir and Hugon — among the first inventors of gas engines — arrived at the same idea: injecting water directly into these engine cylinders. However, probably because of both the inaccurate knowledge we had then of the phenomena occurring inside such systems, and of coarse measurement apparatus of these days, their idea was not recognised for its primary interest.

Footnotes and references

- Rowe, M. R. and Ladd, G. T., Water Injection for Aircraft Engines, SAE Technical Paper, 460192, doi:10.4271/460192, 1946. ↩

- Zima, S., Internal Combustion Engine Handbook, chapter 1: Historical Review, SAE International, 2004. ↩

- Lawton, B., The Piston Engine Revolution, chapter 9: Some Early Internal Combustion Engines, The Newcomen Society, 2011. ↩

- Heywood, J. B., Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals, McGraw-Hill, 1988. ↩

- Slade, F. J., The Lenoir gas engine, Journal of the Franklin Institute, 81(3), pp. 175-179, doi:10.1016/0016-0032(66)90172-4, 1866. ↩

- Lenoir, J. J. E., Moteur à Air Dilaté par la Combustion des Gaz, Brevet n°1BB43624(4), 1861. ↩

- Clerk, D., Gas and Oil Engines, Longman Green & Co, 1897. ↩

- Hugon, P., Improvement in Gas-Engines, United States Patent 49346, 1865. ↩

- The difference is crucial in this context. Steam being already vaporised, no latent heat of vaporisation can be used to absorb a fraction of the chemical energy released by the combustion process in order to control it. Furthermore, the resulting increase of water specific volume is responsible for a supplementary pressure applied on the piston. ↩

- Tresca, M. H., Procès-Verbal des Expériences faites sur le moteur à Gaz de M. Hugon, Annales du Conservatoire Impérial des Arts et Métiers, Tome Septième, 20 juillet 1866. ↩